INVESTIGATION: THE APOCALYPSE OF OBJECTS

Reflection on the afterword by David Graeber II Studio Textures

Urban Planning and Design

KTH Royal Institute of Technology

2022

individual work

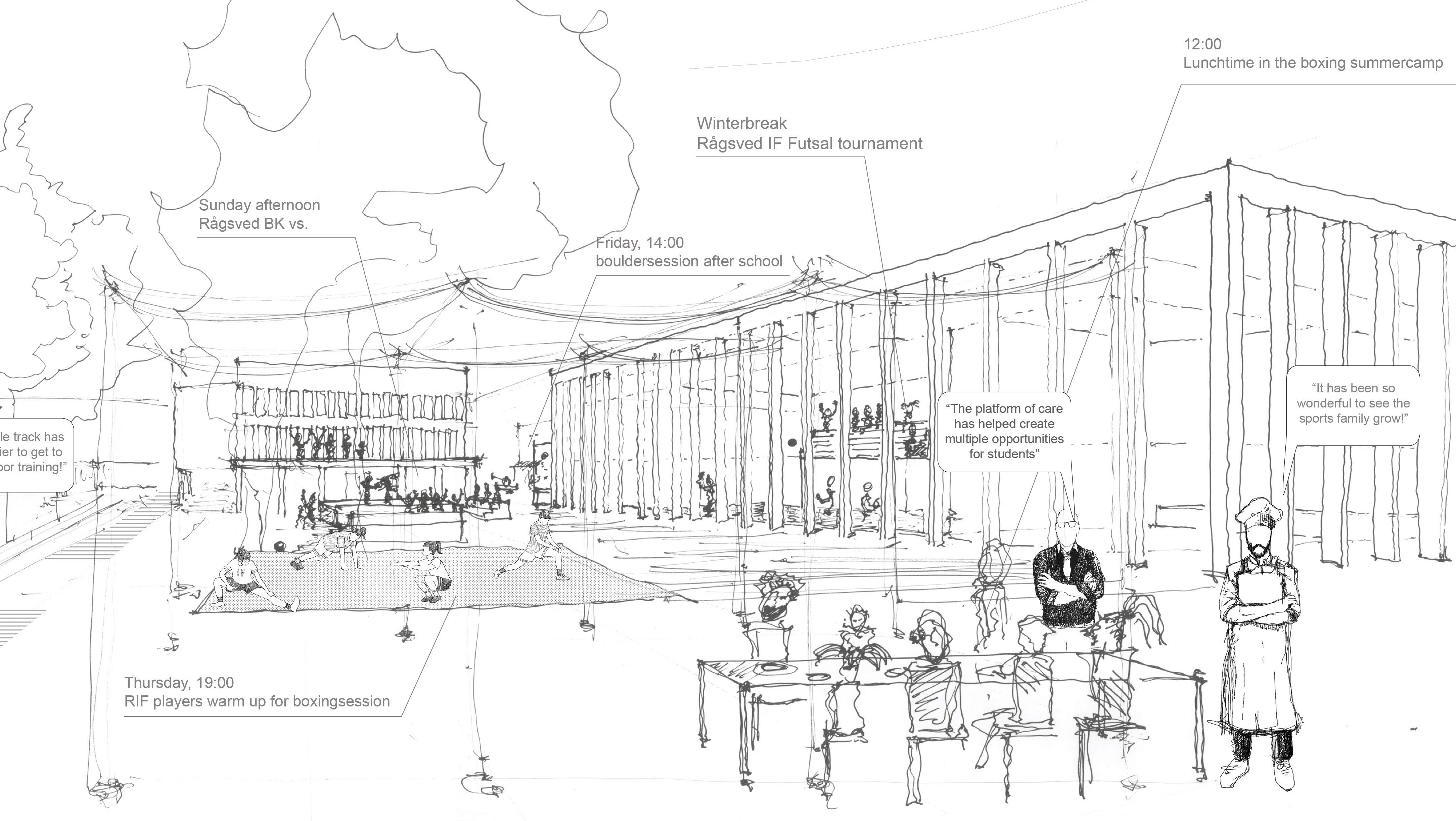

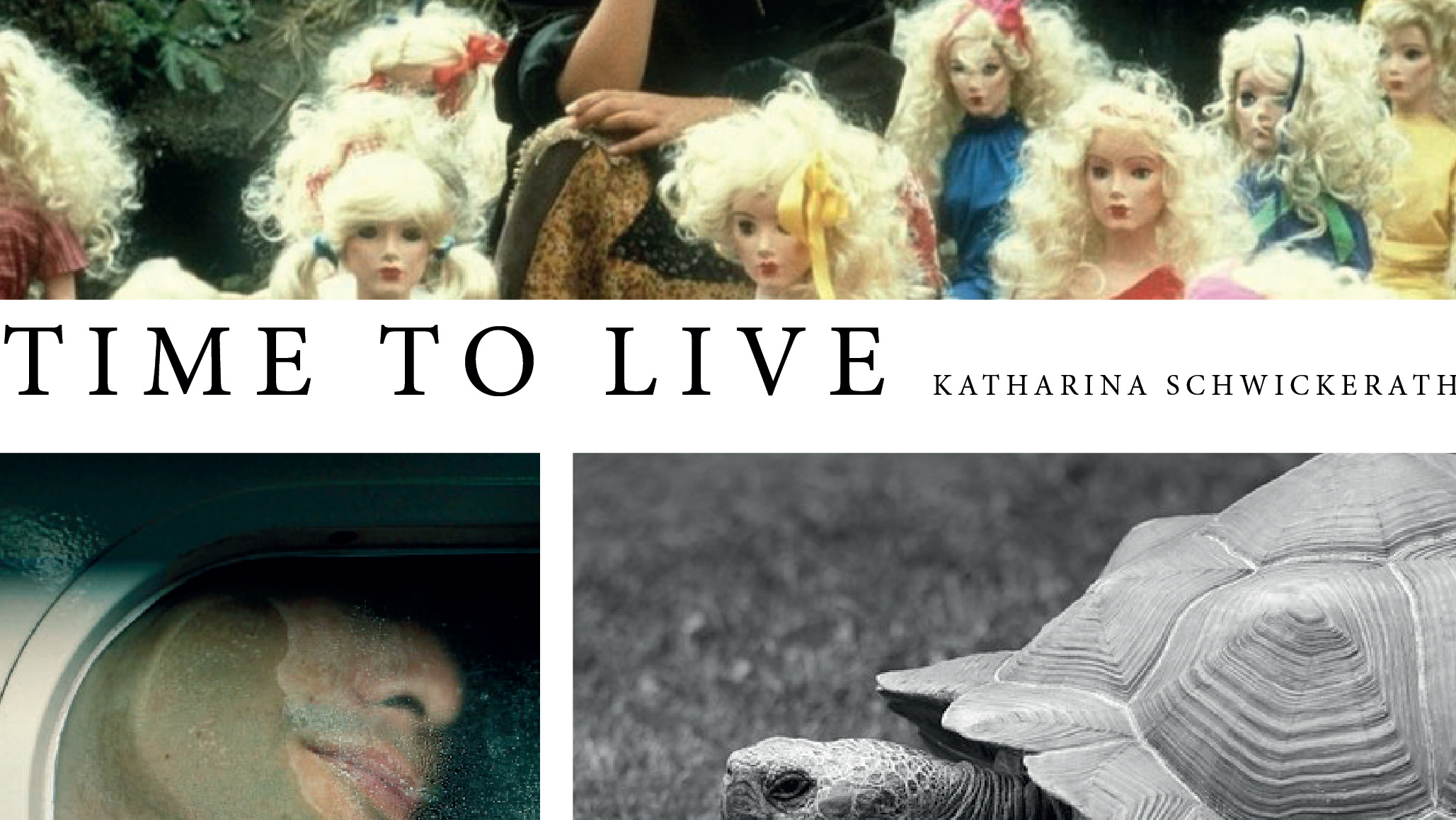

In this essay I explore Graeber's theories in his afterword "the apocalypse of objects - degradation, redemption and transcendence in the world of consumer goods" in In Economics of recycling (2012) and examine them in the context of the TIME TO LIVE project (Investigation IV). I found it very interesting how people in end-of-life care environments look back on their lives. I link this retrospective on life to Graeber's theory.

Hiding away death

In Madagascar, it is considered very exotic that many Europeans have never accompanied a person in dying. If one deals with the topic of birth and death, one notices that the entry into life as well as the exit from life is socially suppressed in the western world today. Graeber states: "We don't like to have to see, or think too much about, the moment when living organisms come into existence, or dissolve away out of it" (Graeber 2012, 277).

Dying has been on people's minds for a very long time. Exiting life seems to be an existential and central theme in almost all cultures. The mystery of how life ends and what happens afterwards drives people and makes them believe in different views and religions. The subject of death is one of the most documented in our human history. The dying process is a very emotional phase for every person involved. To suppress feelings, to be lonely is agonising and makes one ill. In many cultures it is traditional to meet at the funeral, to mourn together, to admit the pain and to process it. These traditional processes help to perceive death as something normal and natural and to accept it as part of life. It is striking in this context that more religious societies have a more open approach to death than secularised societies, where faith and religion are no longer very popular. In Sweden, however, the number of people who are cremated without any funeral directly from the hospital and then scattered by crematorium staff at an anonymous memorial park increases every year. The relatives seem to prefer not to commemorate the death of their fellow human being. Scientific laws are not compatible with the views of religions. Since research has so far been unable to explain what happens after death and no one knows what happens when one is no longer alive, it seems that in societies where nothing is believed that is not scientifically proven, people keep silent, ignore and suppress. In this context, the architect Caminada counters the suppression of death. With the mortuary in a small mountain village in the Swiss Alps, he creates a place where the living can mourn and share the pain of loss. The small wooden house concretises the theme of mourning and stands symbolically, physically and atmospherically between everyday life and the religious district with cemetery and church describes. The people from the village meet there, remember good times together and celebrate the good times they had with the deceased. Life is valued and celebrated. (Caminada 2007, 85)

The phenomenon of looking away and suppressing, of entering and leaving life, can also be found in other areas. You don't want to see animals die either, as Graeber mentions. You are their dead flesh, but you don't want to see their throats cut. That would be considered a nuisance and an outrageous disturbance of the peace. In our world, not only is the birth and murder of billions of animals annually hidden behind closed doors to be swallowed hours later, but unimaginable quantities of goods are also produced in industrial areas on the other side of the world, shipped across the ocean for days to be bought by us and finally disappear again. This constant appearance and disappearance of products goes almost unnoticed and is usually not questioned.

Personification of products

When I was three years old, I asked my mother when the rubbish men were going to bring us new rubbish, because I couldn't imagine the processes and the system of the flow of goods.

What makes it easier to understand manufactured goods is to see them as discrete, self-identical, free-standing entities - according to Graeber.

This view of products as finished things is, as it were, the suppression of production processes. If you perceive a commodity as a complete work, as a self-identical thing, you personify the object. If we humanise a car, for example, we ascribe a character and an essence to it and ignore the fact that the car was produced from metal in many hours of work and assembled with great energy and time. Behind the process of production and also the scrapping of a car are highly complex processes that reflect our highly industrialised society. If we personalise goods and perceive them only as complete, self-contained objects, we ignore the processes that underlie the goods and suppress the consequences of these on our environment.

One sees the object, not the process of growth and decay. Graeber does not address whether this is willful ignorance or indifference, not seeing the processes behind industrial production, or whether the phenomenon is due to the fact that the complexity of the globalised world overwhelms people and they cannot possibly understand all the processes.

The comparison with the birth and death of man would argue for suppression. One can assign people a certain responsibility for not coming to terms with their own existence. The indifferent attitude towards these life-deciding events seems like a selfish tactic to protect oneself from unpleasant situations. One could call it anti-social to stigmatise the individual people who are born, give birth or die.

The situation in which we find ourselves would speak for an excessive demand. As William J. Mitchell describes in Boundaries/Networks, complex global networks affect all aspects of our daily lives. Connectivity has become the defining parameter of our world. Willam J. Mitchell describes "processes" as the relationship between times and networks. (Mitchell, 2010, 235)

These processes, of which both Graeber and Mitchell speak, are so complex and rapid that they increasingly threaten people's health. The globalised, digitalised world has become so fast, complex, competitive and overwhelming that people suffer from stress, depression, imbalance, anxiety, burnouts and other mental or psychosomatic illnesses. I took this problem as the starting point for my urban development project in Gävle.

The theme of my proposal is: slowing down. It intends that people slow down and live their time actively. Constant noise in cities and omnipresent lighting leads to sensory overload. We work all week to recharge our batteries for a few days so that we can keep going and not collapse from exhaustion. We long for the weekends. As part of the BIG project, the University of Gävle is collecting data from the citizens of their city to find out where people like to spend time and feel good in Gävle. I took the map to bad experiences as an impetus to redesign the area around Södra Kungsgatan street.

The elimination of individual traffic, the change of streets to curvy long walking paths should encourage people to walk or cycle. The time measurement of hours, minutes, seconds, milliseconds should move into the background. Spending time instead of saving time is the motto of the proposal. The seasons, natural day and night rhythms should bring people back to a balanced way of life in harmony with nature. For this reason, great emphasis was placed on creating new green areas. Watching grass grow, experiencing weather breaks, sensitising people to day and night as well as seasons and sharpening their senses leads to calming down and learning not to feel disoriented and stressed when not being effective and fast, not to survive or live through - but to learn to live time. Round community houses are meant to be places of protection from sensory overload. In the houses, everyone can sharpen their senses for nature, relax and unwind, or meet friends and maintain social contacts. Slowing down everyday life also means that being together has a place in life again. Because we don't have to reach our goals in the shortest possible time, we have the serenity to socialise, which is another cornerstone of a healthy society. To counteract sensory overload, all neon signs are removed. Only necessary, actively designed light is provided.

Cosmologies with consequences

While I have focused on the health consequences of globalisation, Graeber mentions global environmental degradation and climate change as a consequence of the global industrial system. Building on this, he explores some of the reasons why past efforts to address climate change have been woefully inadequate. He suggests that a misleading worldview is the reason we are not acting sufficiently to stop the scale of destruction caused by the system. He discusses the worldview underlying the economic system and the related models of recycling and environmental sustainability. In this context, he highlights two aspects that are part of this worldview and therefore, according to him, also root causes of the current crises.

First: is the image of a self-identical object that just magically appears and disappears again.

Second: is the image of the cycle in the context of both products and human lives.

On point one:

Graeber's observation that our contemporary society focuses on self-identical objects rather than on the processes and what one does could be reversed. Then the idea would be to focus on verbs instead of nouns in life. Besides confronting industrial production processes, we could also increase the individual quality of life with this attitude of seeing life as a process. Emphasising the experience in time and valuing human relationships could be an approach to move away from a consumer society and to focus on other values instead of material values. Focusing on action, on Doing, could work as an individual approach to life for each person. In the following, I will briefly reflect on how the reinterpretation of the thought model could affect the way we look at our own lives.

In this context, it is very interesting to change perspective and look back on life from the point of view of an end-of-life care patient. If you deal more intensively with people who are about to die and can consciously prepare for the end of life, you gain valuable insights into what really counts in life in the end. in the face of death, people tell us what moves and concerns them. According to Kübler-Ross, these are never material riches. Her patients do not reflect on how many fur jackets or handbags they have owned, but one reflects on memories in life and relationships with people. Many reflect on deeper meaning. The medical director, who has had many conversations in the face of death, sums up that in our materialistic and competitive world there is little time to reflect on a deeper meaning of life. If one were to learn from end-of-life care patients and their perspective, then one would appreciate the value of interpersonal relationships and beautiful experiences more and could actively improve the quality of life from this insight. (Kübler-Ross, 1973, 158)

This was also the starting point of my investigation. At the beginning of the Time to Live project, I engaged with end-of-life care patients and tried to learn from their perspective on life and to plan cities based on this knowledge so that people have an increase in the quality of life in their present.

On point two:

Graeber asks why both trajectories are seen as circular, as cycles.

Graeber makes no distinction between circular and cycle in his question. However, a cycle does not necessarily have to be circular.

Suppose his cycle is circular. A circle has no beginning and no end. This would mean circulating infinitely, which would make the word recycle superfluous. A circle has no end and no beginning. a circle can also continue infinitely. The process of painting a circle has much more of a beginning and an end, which brings us to the subject.

What seems to be important is not the motif of the circle itself, but the process of painting, which translates as the process of life. The image of a circle of life suggests that the path is already predetermined, namely round and ending where one began to paint. This suggests a determined view of the world. This image leads to people having the impression that their life path is predetermined. It ends where it began and circulates at the same angle until one disappears into nothingness again. This determination could lead to people's actions becoming passive, because the orientation model pretends that one cannot actively shape one's lifetime. But being passive also means not taking responsibility for one's own actions, which can lead to reckless behaviour towards fellow human beings and nature. Exactly these consequences are reality. We seem to reflect this model very well, or the model reflects us well.

In his discussion of the image of the cycle, Graeber explains that people do not grow up and grow down in the course of their lives, as the "life cycle" suggests. Rather, life is like a long ascending arc with a final crash. The only parallel with the cycle is that you end up where you started - in nothing, says Graeber. It is the same with the image of an object in the cycle.

I find Graeber's view of life interesting. He criticises the model of a cycle of life as flawed and immediately corrects the picture. In science, a curve is always linked to coordinates and parameters. Under these conditions it rises or falls. The parameters that Graeber uses in his arc are: social prestige and power. Here he adopts the conventional characteristics by which we humans are measured in today's meritocracy. It may not have been Graeber's intention to show these values per se, but only the flawed image of life - nevertheless, in my opinion, these very parameters are another fundamental flaw in our world view, which also has dire consequences.

If you look at other qualities of a person than social prestige and power as valuable, the curve would look different. For example, if we look at the amount of knowledge a person possesses - it is quite possible that the curve rises steadily before death, assuming one does not forget much, which would again illustrate the individuality of the curves and thus of human lives.

If you look at life from the perspective of an end-of-life care patient, it becomes clear that these values of prestige and power, which occupy us a lot in life, completely recede into the background at the end of life and fundamental questions about the meaning of life, as well as the relationship to other people, become much more important.

Ideological images equilibrium and endless productivity

In the rest of the section, Graeber looks for the causes of the flawed worldview. According to his theory, the reason why we maintain these fantasies is due to our market system, which is based on the idea of property rights that assign values to objects. Since the logic of property is that something moves and changes and yet remains the same - it supports the ideological image of things moving in a cycle.

In the following, Graeber traces the historical development of this worldview back to its origin, the oikos, the ancient ideal of a self-sufficient household. The family farm is self-sustaining and in balance with nature, as nothing is bought and nothing is thrown away. in his ideal, the oikos is thus ecologically sustainable and at the same time economic, as produced goods are sold to enable the paterfamilias as a free man to participate in politics, so that he represents the interests of the family.

This ancient ideal is based on slave labour and hierarchical structures within the family, and it leaves some questions open as to whether the oikos system could really have worked. For example, one wonders to whom the family could have sold goods if everyone lived according to this ideal and therefore there was no need for consumption. But if you look at the oikos model as an ideal and more abstract model with an exemplary function, i see that many aspects, such as social security and ecological sustainability, have been considered. The space for democratic participation is also given a high priority. The family's goal was to manage the economy in such a way that the man (even if only a partial democracy) could participate fully autonomously, freely and independently in the political life of the city and make decisions in the interest of the family. The primary goal was therefore freedom and influence, which was to be guaranteed by commodity production.

In David Graeber's lecture on a fair future economy, the anthropologist talks about precisely this significance in democracies: participation. (Graeber, 2015)

The oikos, the family estate, combines economy and ecology (the economy of nature).

With the industrial revolution, the ideology changed from a producing unit to a consuming unit. The central object became commodities, which ran in a kind of life cycle from production to destruction, as Graeber states. Instead of a balanced relationship within the household and with nature, modern economies focus on the constant growth of the economy, which means a constant increase in production and destruction. Graeber notes that the concept of a cycle of production and destruction is strange rather than appropriate. Considering consumerism and the mountains of waste we produce every day, I have to agree with Graeber on this. He talks about the tension between endless productivity and a self-contained system, which occupies both the economic and the ecological discourse on a moral level. Productivist approaches seem to alternate with equilibrium models. Graeber notes that the image of economies as closed loops hardly does justice to the continual trade and points to an even more extreme discrepancy, namely that not even our ecosystem would be able to function in closed loops, since life on earth is directly dependent on the sun's energy-producing rays. If we consider that our economies are dependent on a dwindling supply of oil, coal and other limited resources, we can classify the radical equilibrium model as ideologically unworkable and unrealistic.

In this context, Graeber explains the recycling model. It is, in Graeber's view, simply another attempt to maintain the worldview of a circular, balanced model in a system that does not even begin to have anything to do with balance. The concept of recycling, according to Graeber, is dependent on the logic of property. As elaborated earlier in the text, the image of the circuit suggests that the commodity circulates as a self-identical object in this circuit and yet remains unchanged.

However, since in our system commercial value must be created in order to have a growing economy, this object must leave the household and be sold. Only trade in the goods, economic transactions between different households, creates value. Simply reusing or giving away the product would be reuse, as Graeber notes, and would not increase a country's GDP.

But what happens when GDP stops rising?

The gross domestic product, although imprecise, is the indicator of economic performance of an economy. If it does not rise steadily but stagnates, the production processes in a country are in decline. Economists and politicians stare at the gross domestic product, to which statisticians add everything that is created and achieved in an economy - as long as it has a price.

If you don't grow, you die. This is a reminder that many economists address to politicians. The fear of stagnation, recession or even depression of the economy is great, as the consequences would be massive. If you think in free-market terms, it is a disaster - we would probably not be able to continue the way of life we have today. If the economy does not grow, the pressure on the labour market would increase massively, unemployment would rise. Because tax revenues would decrease, social benefits would be cut. Everyone would become poorer and the poorest in our society might not be able to meet their basic needs.

This scenario became a reality in 1929 with the beginning of the New York stock market crash. There are many views on what led to this, but ultimately risky speculation, banking crises, deflation, panic and wrong or no political countermeasures such as emergency loans or government bonds led to the Great Depression. In many countries, the Great Depression of 1929 was a time of misery and poverty. Ultimately, the great hardship of the people led to political radicalisation, which was a decisive factor in Hitler seizing power. There is widespread agreement among historians that the economic crisis in the USA was brought to an end by his rearmament policy before the Second World War. Roosevelt's New Deal stimulated the economy through government job creation measures and increased arms production. With these measures, the economy recovered and a period of economic recovery was ushered in. Economic growth generates wealth, it is the driving force for innovation, for work, higher incomes and offers the opportunity to improve one's standard of living, to escape poverty on one's own through work and diligence and to realise oneself - this is the idea of capitalism and is supported by ideologically charged theories such as the American dream. Looking at post-war Germany, this connection between economic growth in a market-integrated system and an increase in prosperity becomes particularly clear. With loans and investments, the USA stimulated the economy in West Germany within the framework of the Marshall Plan, and supply and demand also increased. In the Cold War and the related battle of economic ideologies, the West was the clear winner. Especially in Germany, where there was a direct border between the two systems, the difference was particularly extreme. The capitalist system was more attractive: consuming and working one's way up to success, going on holiday in one's own car, watching TV in one's own flat in the evening and moving up in one's job made dreams come true, satisfied desires and contributed to people's rising standard of living. Growth is therefore not an end in itself, but should bring higher incomes, the possibility to realise life plans and consumer desires.

Why does Graeber nevertheless believe that we need to fundamentally reform the economic system?

In the post-war period, economic growth may have been closely related to rising living standards. In recent years, however, these material consumer goods have no longer raised living standards to the same extent. It seems that our desires are no longer so great and our needs are satiated. To continue to generate economic growth and create value, production and sales would still have to continue. Since childhood, we have been taught that our self-worth and social status rises and falls with the purchase of products. In addition, Western companies are looking for markets (for sometimes inferior goods and waste) in poorer countries in Africa and Asia and are destroying the local economy there. In addition, wars and natural disasters - as long as they are not in the home country - cause GDP to rise. Once everything has been destroyed, a lot has to be produced and built - a profitable market for the USA in the post-war period was, for example, West Germany. Wars and catastrophes, as well as worse living conditions OTHERWISE, therefore lead to GDP rising and the economy of a country doing well. It seems that people are looking for ways to destroy in order to produce again. Unfortunately, there are many examples in global political history of wars that have to do with economic conflicts of interest and market problems. In the cold war, rearmament was a central issue. It is also interesting to note the links between Afghans and Americans after the collapse of the Soviet Union. the USA had already supplied weapons to numerous countries in the Middle East; against the Tailban, for example, they later fought again with the same weapons and also supplied their opponents with weapons. The US economic system is based to a very large extent on the arms industry. Another reason why the market system promotes inequality and produces social division is the one-sided and unbalanced view of what kind of work is valuable and what is not. As Graeber mentions, political economy starts from the assumption that value is primarily a power of creation, with only very few people in society actually involved in the production of value. Everyone else, according to Graeber, works to keep the material goods that have been transformed that way. Another large part of society is engaged in social work and caring for other people.

So the economic system itself generates this one-sided view of the production of goods and prioritises the objects and the work with the objects as creating value, while the other system-relevant work is invisible.

My project unfortunately does not delve deeply enough into the people who live in the Gävle area and what they do for a living. However, Graeber points out the urgency of bringing precisely this diversity of occupations to the forefront and addressing and considering all work in the future. Only when you include all people in a society in the system do you create balance and prosperity. The corona crisis has made many of these invisible labours visible and shown that they are indispensable and relevant to the system. Therefore, they must be included in future plans.

How much does economic growth still have to do with prosperity?

The issues addressed in this essay suggest that the negative effects of the economic system now predominate. The destructive nature of the system seems to be getting out of hand. We seem to have lost control in the face of the complexity of a global economy. The symptoms and consequences that Graeber describes in his essay are signs that we are no longer doing well in this system. Graeber sees a crucial problem for these developments in the constant attempts to suppress the extent of the system by making it easy to overlook and ignore the imbalance of the system through artificial images and models.

In my project, I looked at the overwhelming symptoms and consequences of the economic system on people. My initial realisation was that it seems to suffer from the fact that its complexity overwhelms people and makes them ill themselves. I therefore looked for solutions so that people would no longer be so exposed to the stress of productivity and the consequences of consumer society. My goal was to enable them to reflect on values that have nothing to do with their ability to perform or are defined by material things, but instead focus on people and their well-being.

I find Graeber's discussion very enriching. He gets to the bottom of the origin of the images and tries to understand where these ideological models come from. He places the recycling model in a series of ideologies that have the goal of supporting the system and reflecting it at the same time. In view of the negative influences that the system has on us humans, he believes that we must overcome these ideological ideas and begin to completely reconfigure the categories of the economy.

graeber's essay has made it even clearer to me that we urgently need to address a post-growth economy. Growth seems to be doing more harm than good. There are many approaches, from relocalisation and de-globalisation to the reduction of working hours and an independent basic income. the time to live project and the reflections from the perspective of end-of-life care patients are closely oriented towards people. Graeber concludes his lecture "on a fair future economy" (2015) with the statement that you have to ask people what they want. I find this approach very inspiring and instructive. In order to rethink our economic system, we need to break free from conventional thinking, from previous worldviews, from images and ideologies, and involve all stakeholders instead of just a small part of society. It is a matter of decoupling the word prosperity and living standards from consumerism and productivism and putting people and their relationships with each other at the centre, so that we can continue to live in harmony with nature and our fellow beings on the planet in the future.

REFERENCES

Caminada, Gion. 2007. „Meaningful Architecture in a Globalised World“ in The Architect, the Cook and Good Taste, edited by Hagen Hodgson, Petra; Toyka, Rolf, 82-93. Berlin/Boston: DE GRUYTER

Graeber, David. 2012. „ Afterword: the apocalypse of objects – degradation, redemption and transcendence in the world of consumer goods” In Economics of recycling, edited by Catherine Alexander and Joshua Reno, 277-290. London/New York: Zed Books Ltd.

Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth.1973. “Life and Death: Lessons from the Dying” in To live and to die, edited by Williams, Robert Hardin, 150-159. New York: Springer Science+ Business Media.

Mitchell, William J.2003. “Boundaries/Networks” first appeared in Me++: The Cyborg Seif and the Networked City, 7-17. Cambridge: MIT Press